Mississippi State's Cloak-And-Dagger Trip To "The Game Of Change"

In 1963, Mississippi State was forbidden from playing in the NCAA Tournament due to the skin color of their opponent. But they did it anyway. What should we make about the myth surrounding this game?

Thanks for checking out the Ball and Order Newsletter. We do a lot of cool stuff, mainly related to sports history, the WNBA and the NBA. We’d really appreciate your support, so please subscribe with the button below, check out our podcast, and follow us on tik tok: @ballandorder.

The NCAA Tournament will begin in earnest tomorrow with one of the best spectacles in sports. Upsets, buzzer beaters, and near-escapes by favorites make the first round of the NCAA tournament so much fun. But the more important games happen a little later when teams punch their tickets to the Elite Eight or the Final Four. However, none of these games will come close to the importance of the 1963 Midwest Regional Final between Loyola-Chicago and Mississippi State.

The matchup became known as “The Game of Change” because of its implications for integration in sports. Loyola-Chicago is a program that you are probably familiar with from their 2018 Final Four Run and Sister Jean’s stardom. In 1963, Black players Jerry Harkness, Vic Rouse, Les Hunter, and Ron Miller started for the Ramblers and broke an unwritten rule that only three Black players could play at the same time. They were dominant all year, went 24-2, and reached the top 3 of the AP poll. In the first round of the ‘63 tournament, the Ramblers beat Tennessee Tech by the largest margin in the tournament history, 111-42.

Loyola-Chicago’s team is a fascinating story, but I want to talk about the other side of the Game of Change and Mississippi State coach Babe McCarthy. McCarthy came to MSU, his alma mater, in 1955 right after Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky teams reached their peak with three national titles in four years from 1948-51. McCarthy quickly built a winner in Starkville and the Bulldogs won the SEC crown for the first time in 1959.

However, the state of Mississippi prevented the team from participating in the integrated NCAA basketball tournament due to their long-standing goal to be the most racist state in the country. So the 24-1 Bulldogs were banned from competing for a championship in ‘59. The same thing happened to the 1961 and 1962 SEC Champions Bulldogs. Of course, Adolph Rupp, a notorious racist even for the time, and Kentucky played teams with black players in order to reap glory. At the same time, hated rival Ole Miss was able to win “championships” on the gridiron since they did not have to play integrated schools to claim them.

By 1963, McCarthy and the university had had enough. After the Bulldogs secured the SEC championship, MSU president D.W. Colvard announced that the school would compete in the NCAA tournament “unless hindered by competent authority.” McCarthy cheered the decision and had the support of the student government, the Starkville community, and even the Mississippi School Board. However, he also didn’t think “our president’s decision has anything to do with the situation in the state of Mississippi.”

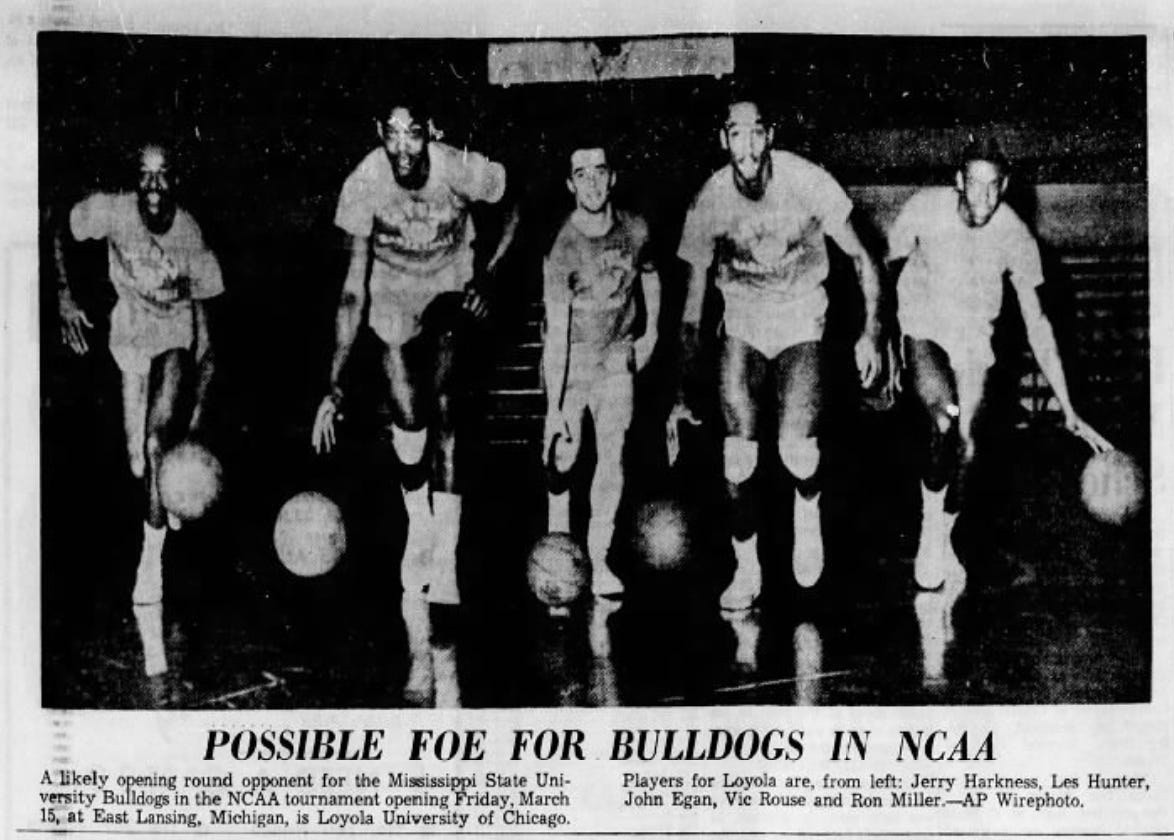

And boy, was he right. Governor Ross R. Barrett vehemently opposed the team playing Loyola. State Senators Billy Mitts and B.W. Lawson got an emergency temporary injunction to stop the team from going to the tournament in East Lansing, Michigan.1 The Jackson Clarion-Ledger even ran this photo to show exactly who MSU would be playing and, maybe, scare some readers.

McCarthy and Colvard met in barns around Starkville to devise a clever ruse. To prevent the injunction from being served, Colvard, McCarthy, and the assistant AD all left Mississippi in the night. Then, a decoy group of reserve players and trainers went to the Starville airport, while the more important players remained in their dorms waiting for a private plane that would reunite them with McCarthy. A sheriff named Dot Johnson, went to the airport to serve the injunction but gave up quickly.2

The Bulldogs were now free to meet up with McCarthy and go play Loyola. As the team flew out of state, a player commented “Now I know how those East Berliners feel when they make it past the Wall.”3 The Ramblers crushed Mississippi State by 10 en route to a championship. It seems like playing black athletes was helpful in winning titles!

But the key moment came before the game when Jerry Harkness, Loyola’s black captain, shook hands with Joe Dan Gold, MSU’s white captain, at center court. Harkness told NPR in 2013 that the camera flashbulbs going off during the handshake made him realize that “this was more than just a game; this was history being made." Many say that the game had a massive impact on college basketball, and even on university integration itself.

The photo, McCarthy’s great escape, and Loyola’s magical run made for one of the neatest stories in college basketball history. McCarthy would go on to become one of the best and funniest coaches in ABA history. He was raised in a tiny town in northwest Mississippi and earned the nickname “Ol’ Magnolia Mouth” because he “had a wonderful Southern accent that made him sound like Charles Laughton in Advise and Consent.”4 When McCarthy was the coach for the floundering Memphis Pros, he was hit by a car in the parking lot while telling a story to a scout. After getting up, McCarthy said “bad enough that I have to coach this outfit in Memphis, now somebody’s trying to run me over in the damn parking lot.”5

McCarthy also earned a lot of cache with Black players because of the Game of Change and treating them with basic human kindness. For example, Steve “Snapper” Jones said that his only saving grace of being a Black player in New Orleans was McCarthy, his coach, treating him with respect. At the same time, Jones and other Black players were denied housing in New Orleans due to the color of their skin.

While McCarthy seems like a genuinely kind and pleasant person, I’m not sure how much stock we should put in the “Game of Change” as a cultural milestone or how much credit McCarthy/Mississippi State should get. Basketball certainly can have an impact on the real world, but as Kevin Blackistone points out this particular game didn’t change much.

The game didn’t change attitudes toward race in Mississippi. MSU would allow its first Black student in 1965 with little attention, but James Meredith still needed the protection of US Marshals to attend the Ole Miss. In the years after the game, white Mississippians still murdered many civil rights activists including Medger Evers and Veron Dahmer. Martin Luther King would be condemning atrocities in the state until he was assassinated in 1968.

Furthermore, McCarthy and the MSU Athletic Department were merely acting in their own self-interests. He just wanted to play a basketball game, go for a championship and maybe stick it to the man. Perhaps If Mississippi State could win championships without playing Black players (like Ole Miss’s football team did), McCarthy may not have been so intent on playing against Loyola-Chicago.

“To be clear, this was not an act of heroism on the level even of a single black Mississippian trying to register to vote at the time,” MSU Professor James Giesen told Blackistone. It’s absolutely true. As Blackistone mentions, the narrative around this game may serve “to whitewash history rather than preserve it.”

But that doesn’t mean it’s not a good and interesting story! Or that McCarthy isn’t a fun character who treated people with respect. In sports, we too often make a myth out of a tale. I don’t think we have to do that here to appreciate McCarthy’s exploits or the will to play basketball in the face of challenges.

How they got an injunction based on an unwritten and therefore unenforceable law is a monument to racism.

A historian described him as “a deputy sheriff who tried to do his duty, but not too hard.”

I got this nugget from Miracles on the Hardwood by John Gasaway.

As a sidenote, please read the plot of Advise and Consentwhich is Charles Laughton’s last movie in 1962. It centers around the Senate confirmation hearing of a Secretary of State and multiple politicians end up dead.

These stories all come from Loose Balls, the funniest book I’ve ever read.